Times Square was packed. Even by Times Square standards.

Less than 24 hours after George Zimmerman was acquitted of murdering unarmed black teenager Trayvon Martin, two very different rallies were staged in New York City.

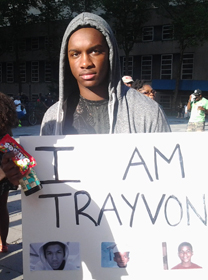

The first saw a crowd of thousands marching from Union Square to Times Square.

They carried placards and skittles, while some were brave enough to wear hoodies in the blistering July heat.

Simultaneous protests broke out across Florida, Boston, and Washington DC.

Most of them, with the exception of Oakland, California, were peaceful, a far cry from the “riots” that had been predicted on social media.

“The system is racist, we’re not gonna take it,” they shouted through bullhorns. “No justice, no peace!” they chanted.

“We’re here to show that black lives have value too!”

On Twitter

Protests rang out on social media as well.

Bennet Roach, a journalist with the Montserrat Reporter, tweeted: “This case will change America!! If evidence was inconsistent in reverse verdict would be the reverse.”

For Trinidadian soca singer Fay Ann Lyons, who also took to Twitter after the verdict, it was a time of introspection.

She engaged with her fans on Twitter for more than an hour about the verdict. At one point she tweeted, “Soooo hear nah... Does this now mean we have to be careful wearing hoodies or just careful being black, unarmed and wearing hoodies??”

As a performer who spends much of her time performing for the Caribbean diaspora in Florida, Faye Ann Lyons praised the decision but knew that she couldn’t do the same.

“He's Stevie he can make that move and significance would be recognized persons not from USA can't,” she tweeted to Caribbean Intelligence.

“It takes a certain amount of self sacrifice to make a move like that not knowing if it will make an impact at all.”

Caribbean protesters

Even though Brooklyn is home to New York’s largest Caribbean population, they didn’t display their presence with the usual parade of flags.

Once the speeches calling for federal charges to be laid against George Zimmerman ended, the stragglers who hadn’t gone on to Union Square picketed the Hall.

“Take this case to federal court, justice for Trayvon!”

A distinct Trinidadian accent rose above the chants, shouting back, “What difference does it make? We’ve been chanting and marching like this for years, what has the NAACP done?”

The 69-year-old Trinidadian asked to be identified only as Youssef Hamid.

Legal response

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) launched an online petition immediately after the not guilty verdict was read on Saturday 13 July.

As of 18 July, more than

475,000 people had already signed, overwhelming the website at times.

Personal view

Yousef Hamid also took issue with speakers who blamed the prosecution for presenting a poor case.

All he saw, he said, was a blatant case of racism in a country with a long history of racism.

He couldn’t see any alternative to the demonstrations, but pointed to the Egypt protests as an example of a system-changing social movement.

Mr Hamid has been in the United States since the 1970s.

He claims to have had his share of racist encounters, but when asked if, being from the Caribbean, he saw himself as different from the stereotypes attributed to African Americans, he scoffed.

“That’s probably what your parents or the older generation used to say: that we not like them, they on food stamps. Well, we all on food stamps catching ass now,” he told Caribbean Intelligence©.

The Caribbean experience of racism

A 1998

study by John Ogbu , a professor of Anthropology at the University of California Berkeley, found that black immigrants (from the Caribbean and Africa) found greater success in the education system than African Americans.

This was because they often chose to live in more racially diverse neighbourhoods.

It was also because they lacked a connection to the US black community and “trusted white institutions more than non-immigrant blacks”.

The study goes on to say that it’s not that these immigrants have embraced whiteness, because they still hold on to their culture and traditions. Instead, they don’t reject characteristics simply because of their being seen as “white”.

There, the main character, a bi-racial man, rejects his black heritage after witnessing a lynching. He wonders why anyone would want to be part of a culture where its people are expendable.

Stephen Casmier is a professor of literature at Saint Louis University in St Louis, Missouri.

He has taught courses on post-colonial literature that touch directly on the black Caribbean identity.

Like Mr Hamid, Prof Casmier sees why the Caribbean population may not want to identify with the African American culture.

“The American melting pot always worked on this principle: people melted together because they were not the lowest of the low - black people, or niggers. Who would blame anyone if they could somehow avoid this status?” Prof Casmier asks.

He goes on to say: “We, after a generation or two, we are really all the same. The issues are the same. I wonder why anyone of African descent who has somewhere else to go would come here.

“The risk has always been high of re-enslavement. And it's still high through a mass incarceration system that targets African and Latinos.”

Stop and frisk

The Trayvon Martin protests in New York doubled as a protest against the highly contentious stop-and-frisk program, where police officers can stop, question and search someone they deem to be suspicious.

Raquel Irizarry, who works as a volunteer for the Police Reform Organizing Project, handed out petitions to end stop-and-frisk.

She was armed with statistics, ready to recite them to anyone who asked.

“In 2002, when [Mayor Michael] Bloomberg took office, 97,000 people had been stopped, the majority of them were black and Latino,” she bellowed.

“In 2011, 724,000 people were stopped.”

For example, in New York’s 6th Precinct (Greenwich Village and Soho), 77% of the stops involved blacks and Latinos, even though they comprise only 8% of the residents.

It does not distinguish between Americans, born or naturalised, and immigrants, or even visitors.

“Unless you’re wearing a Haitian flag, they [the police] won’t know where you’re from. You were just stopped while being black,” Ms Irizarry said.

The report does state, though, that the highest percentage of innocent people stopped and frisked came in the 70th Precinct (Flatbush), where 95% were innocent.

Overall, this area ranked as the ninth most searched district, with 11,248 stops in 2012.

There are commentators who will justify New York’s stop-and-frisk, such as Richard Cohen of the Washington Post,

who wrote, “After all, if young black males are your shooters, then it ought to be young black males whom the police stop and frisk.”

For Prof Casmier, that kind of comment poses a fight-or-flight dilemma. He argues that the black population can continue to struggle to have their voices heard, or they can leave.

“Maybe you Caribbean cats with power at home can make a place for us, and welcome some of us to come in out of the hate and live on your islands,” he said.

“Because this place is cold and after all this time, it is only incrementally getting better.”