By Debbie Ransome

Going beyond the basic storyline to dig deeper into the Haitian reality and how it gets reported, this

By Debbie Ransome

With a varied musical soundtrack, interactive areas and well-researched archive material, a new exhibition at the British Library in London seeks to chart the impact of Caribbean and African sounds on the UK's music scene.

From classical composers in the 1700s to soca, steelpan and Notting Hill carnival, the exhibition Beyond the Bassline: 500 years of Black British Music, which opened on 26 April 2024, offers a timeline of Black music and its influence on British music from punk to garage.

The exhibition trail starts with a 1511 Tournament Roll, referencing the earliest recorded UK musician of African descent, John Blake, who played trumpet in the court of King Henry VII. The written record of the Tudor musician's role had been gathered by a 2015 archive project.

One of the most well-known early Black musicians in Britain was Charles Ignatius Sancho. Born a slave in 1729, Sancho escaped, gaining financial independence to become the first known African with voting rights in Britain. A book of his letters showcases his life in 1780s Britain as an abolitionist and writer, as well as the first African composer to publish music in the style of Western classical music.

Following an array of books from gifted violinists, other musicians and composers in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the early history part of the exhibition showcases Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, born in 1875, who became one of the most celebrated musicians of his age, sometimes writing music inspired by African and "Negro spiritual" influences.

Entering more recent times, the exhibition includes early film footage of Trinidadian jazz pianist Winifred Atwell (1914-1983) and the popular caberet performer, Grenadian-born Leslie 'Hutch' Hutchinson, who performed in Paris, before the future King Edward VIII and allegedly had an affair with Lady Edwina Mountbatten. The exhibition films grow more plentiful, reflecting the 1950s stars, including The Southlanders, already mentioned by Caribbean Intelligence © in another article.

Entering more recent times, the exhibition includes early film footage of Trinidadian jazz pianist Winifred Atwell (1914-1983) and the popular caberet performer, Grenadian-born Leslie 'Hutch' Hutchinson, who performed in Paris, before the future King Edward VIII and allegedly had an affair with Lady Edwina Mountbatten. The exhibition films grow more plentiful, reflecting the 1950s stars, including The Southlanders, already mentioned by Caribbean Intelligence © in another article.

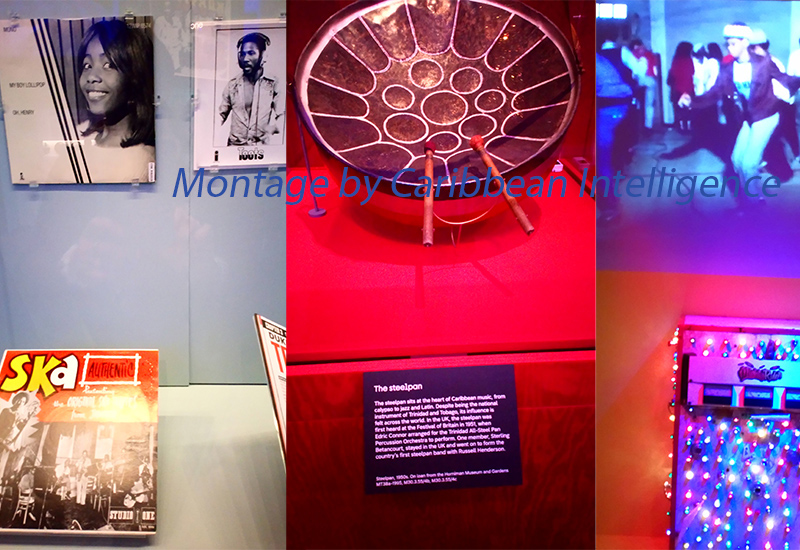

Musical scores, singles and record covers abound as the exhibition trail introduces the visitor to Jamaican guitar star Ernest Ranglin, Trinidadian Rupert Nurse and pan-Africanist Sam Manning. There's the inevitable steelpan, first heard publicly in the UK at the 1951 Festival of Britain.

Music and the Church is reflected on the way to the great names of Black music who made a popular impact in Britain - from Desmond Dekker to poet LInton Kwesi Johnson and an invitation to "rock down to Electric Avenue" in Brixton.

The exhibition does not restrict its archives to London, including a look at Birmingham roots reggae band Steel Pulse, who became the first non-Jamaican group to win a reggae Grammy.

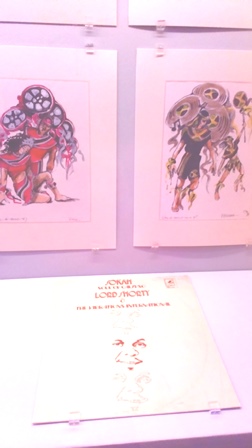

Be prepared to move as the exhibition picks up the beat with a roots reggae booth area, while headphones allow you to hear how then soca godfather Lord Shorty (later becoming Ras Shorty I) built up the layers which would become soca music. There are many posters, pictures and costumes from carnivals in Notting Hill, Leeds and St Paul's in Bristol.

In the next section, the volume picks up even more with, literally, stacks of record covers reflecting the way record shops showcased the latest tracks from the Caribbean and Africa diaspora. Too many to mention, but names include Musical Youth (Pass the Dutchie) and vinyl from well-known labels, including Studio One, Trojan Records and Island Records. As the rhythms of rocksteady, ska, reggae and dub grew in popularity, some of the labels moved to base their businesses in London.

Scroll forward to the 70s as reggae inspired punk bands and the 2-Tone movement. The exhibition finishes on more recent developments, such as rise of garage and jungle.

Artists approached for their perspective have been appearing on British media platforms in the countdown to the exhibition.

Guyanese-born music superstar Eddy Grant told BBC's Radio 4's Loose Ends that the exhibition allowed him to highlight his own development from his calypso roots to incorporate American and British music influences. He said that Black music and Black people had been a part of the UK fabric from the courts of King Henry VIII right up to the protest songs of the 20th and 21st Centuries. He described how he'd written about what he was seeing at the time, adding that his 1979 hit Living on the Front Line, not viewed as a protest song at the time, might not be played on the radio today.

Lead curator Dr Aleema Grey has been calling for greater access for young cultural researchers to the vast archives in the UK which she and her team used so expansively in this exhibition. She told the UK Guardian: "If this project has taught me anything, it is about the need to educate and to introduce learning around how to preserve and protect archival materials." "Black British music is more than a soundtrack," she told the British Black newspaper, The Voice. "It has formed part of an expansive cultural industry that transformed British culture."

The exhibition and accompanying discussions and appearances at the British Library close on 26 August.

Debbie Ransome is the Managing Editor of Caribbean Intelligence.

By Debbie Ransome

Going beyond the basic storyline to dig deeper into the Haitian reality and how it gets reported, this

[photo: Patti Smith & Winston Rodney, cred Ted Bafaloukos]

In a year of global challenges and fall-out, we at Caribbean Intelligence© have focused on the aspirational side of Caribbean life.