By Debbie Ransome

Going beyond the basic storyline to dig deeper into the Haitian reality and how it gets reported, this

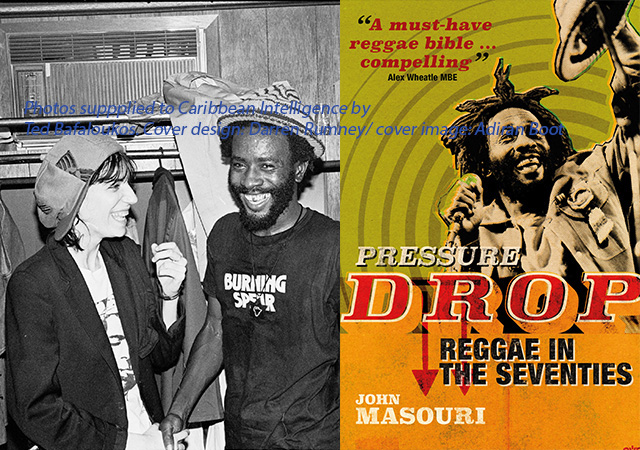

[photo: Patti Smith & Winston Rodney, cred Ted Bafaloukos]

You may reckon you already know the history of Jamaica’s most famous cultural export – but you’ve never heard it told quite like this before.

In his acclaimed new book Pressure Drop: Reggae in the Seventies, veteran journalist John Masouri devotes one chapter to each year of a crucial decade for the island, marshalling a wealth of interviews, anecdotes and events to build up an immersive picture of reggae’s progress from a source of novelty hits to a world-beating creative force.

Previous books about reggae have generally been written from the vantage point of hindsight, but Pressure Drop deliberately creates the effect of events unfolding in real time.

“I wanted to keep my readers in the moment,” Masouri told Caribbean Intelligence©. “If, for example, you’re reading the chapter about 1973, you will never have any reference to what happened in 1974 or in the 90s, you keep it in that timeframe and not, ‘Well, he later died or did this.’

“I think that’s probably different from how other people tell the history and I had a lot of fun doing that.”

During the course of its 624 pages, the book explores the rise to worldwide fame of musical legends such as Bob Marley and Jimmy Cliff, as well as scores of other figures from Burning Spear to Black Uhuru.

But it also places their achievements in the context of the era, with a keen eye on the social and economic turmoil that shaped their lives, for good and for ill. You will hear as much about 1970s political rivals Michael Manley and Edward Seaga as you do about Gregory Isaacs or Dennis Brown.

If you’re an older reggae fan, the saga will send you scurrying back to your crackly Channel One or Joe Gibbs 45s. But it is also aimed at enthusiasts who weren’t even born at the time of these events. Masouri says he wanted to satisfy the curiosity of the younger listeners that he encounters at reggae festivals across Europe.

“They have a lot of information at their fingertips, but they don’t always know how it links up or how the music evolved,” he says.

“I tried to show them how the music developed over that 10-year period. I wanted to convey the sense of excitement that we felt growing up in the 70s, going to a record shop and hearing something new and saying, ‘Wow, who’s this?’ It was a constant journey of discovery and that’s what I wanted to convey.”

As the 70s wore on and Marley became thought of as the first “Third World superstar”, there was no shortage of purists who denounced his growing internationalisation of reggae music, as the book makes clear. But for Masouri, that attitude was quite contrary to the musicians’ own aspirations.

“I’ve interviewed a lot of reggae musicians and I’ve never interviewed any musician who didn’t want their work to be heard by as wide an audience as possible. They wanted their music to be as acceptable as rock or soul,” he says.

“Their dream was to work with Quincy Jones and people like that. That’s why they welcomed people like Herbie Mann and Manu Dibango who came to Jamaica and took their interpretation overseas. It’s the fans who have the more purist view, not the musicians.”

In Masouri’s own career as an authority on reggae music, the 70s was just the start of a journey that he continues to this day.

“In the 70s, I was a fan. I was going to the concerts, I was going to blues parties, I was reading the media and that’s it. I was an outsider,” he says.

But that began to change in the following decade, as reggae gave way to dancehall and the Rastafarian “Back To Africa” rhetoric was replaced by a fixation on the hardscrabble reality of ghetto life.

“In the 80s, I loved that whole shift away from the Marley style towards dancehall. People came along talking about everyday things and came across as something refreshing, something new,” says Masouri.

“I DJ’d in sound systems and in clubs, I got to know promoters. I was writing for Black Echoes, I was very much a participant, and in the 90s ever more so, regular trips to Jamaica, spending time in studios.

“The music was coming from ghetto areas, the dons were running things. I was getting all these early interviews with people at the beginning of their careers. Because people like me had shown that level of interest, we were able to build strong relationships with people and later on, they would remember.

“As a writer, my predecessors interviewed Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, their status was secure,” he says. “I would have prominent writers from previous eras saying to me, ‘Why are you bothering with these people like Yellowman and Frankie Paul? They’ll never amount to the same as Bob Marley.’ But I knew their influence would endure and that drove me to go further into that area.”

So what about the state of reggae and dancehall today? As Masouri told Caribbean Intelligence©, Jamaican music right now is “more fragmented than it’s ever been”.

“Contemporary dancehall doesn’t have that Jamaican character that it had in the days of Beenie Man and Bounty Killer. It’s more like trap music. The similarity to American music has never been bigger,” he adds.

“When I hear lyrics about gang rape, violence and misogyny, it’s very difficult to take, and I don’t cover too much of that.”

But all is not lost, with a slew of reggae hopefuls coming to the fore – represented by names such as Mortimer, Proteje and Kabaka Pyramid.

“I’m very interested in them because they do represent something new and different. They’re nearly all university educated, they’re well read, well informed about what’s going on,” says Masouri.

“They’re very intelligent, far more professional and businesslike. It’s very rare now to be kept waiting two or three hours for an interview as a journalist. They’ve made the genre more accessible to outsiders.

“They have, right from the start, built up networks with producers and promoters all over Europe. Some of the best reggae now is made in Switzerland, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands. It’s a very fertile, truly international thing that’s happened now. This is what’s exciting about the music now and this is what enthuses me as a journalist in 2025.”

Pressure Drop: Reggae in the Seventies by John Masouri is published by Omnibus Press, price £25.

Related articles:

The legacy of Black music: Beyond the bassline

By Debbie Ransome

Going beyond the basic storyline to dig deeper into the Haitian reality and how it gets reported, this

In a year of global challenges and fall-out, we at Caribbean Intelligence© have focused on the aspirational side of Caribbean life.