Fifty years after political independence, dependence remains in T&T and Jamaica

by Tony Fraser

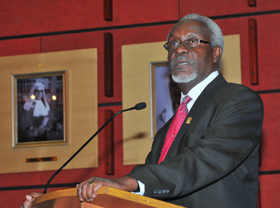

Former Jamaican Prime Minister P J Patterson has criticised Jamaica and Trinidad’s delay in adopting the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) as their final court of appeal.

He said that, after 50 years of political independence, the two most populous and arguably most advanced social, political and economic states of Caricom - Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago - continue to hang on to that most colonial of vestiges, the British Privy Council, as their final court of appeal.

This, he says, is notwithstanding the reality that both countries played significant roles in the establishment of the Caribbean Court of Justice.

“I must say it reflects a lack of confidence in ourselves; which I find disappointing,” Mr Patterson, who was one of the architects in the construction and establishment of the CCJ, told Caribbean Intelligence©.

The former Jamaican leader, who is a lawyer by training, was in Port of Spain for a law seminar of the Caribbean Academy for Law and Court Administration.

International reputations

Mr Patterson said that he found the lack of self-confidence puzzling “in view of the fact of the number of distinguished judges and jurists who have emerged from the Caribbean”.

He noted that many of these international legal experts had sat on the Privy Council itself and had presided at the International Court of Justice and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, working across African judicial systems.

In Jamaica, after many years of refusing to make the CCJ its final court to replace the British Privy Council, the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), in government in 2011 under the leadership of Prime Minister Bruce Golding, indicated that the party would take steps to become a republic and to remove the Privy Council and install the CCJ as the final appellate court.

The opposition’s vote would be needed for a constitutional change, such as setting the CCJ as the final appellate court, as well as removing the Queen as head of state in Jamaica.

However, in June of this year, the new JLP leader, Andrew Holness, having initially agreed with his predecessor’s decision, changed his mind on supporting the CCJ and called for a referendum to allow “the people” to take a decision on replacing the Privy Council.

“I don’t accept that it [a referendum] is a good reason for not supporting the removal of the Privy Ccouncil,” Mr Patterson told Caribbean Intelligence©.

He added: “Having regard to what the Privy Council itself said, it [a referendum] is not a legally required step in accordance with our constitution.”

Mr Patterson also criticised the notion that has arisen in JLP circles that the financial contribution the country makes to the CCJ should be used to establish Jamaica’s own final court of appeal.

“Any such change would require a revision of the [Caricom] Treaty and also undermine the capital base of the CCJ,” he said.

Trinidad: ‘more important things’

In Trinidad and Tobago, the present majority ruling party, the United National Congress (UNC), which was central to the establishment of the CCJ through its then leaders while in power in the 1990s, has also reneged on support for the CCJ after losing office in 2002.

On returning to office in 2010, the UNC, now in coalition with four other parties and led by Kamla Persad-Bissessar, swept aside questions from journalists about the government giving support to the CCJ to replace the Privy Council.

“There are much more important issues, to be honest with you, that will engage our time and our money than determining whether to move away from the Privy Council today or tomorrow,” Prime Minister Persad-Bissessar told journalists immediately after taking office in May 2010.

Like the JLP in Jamaica, the Trinidad and Tobago prime minister said her government would hold a referendum to decide on whether to replace the Privy Council with the CCJ.

However, in April 2012, under political pressure over issues such as allocation of state resources and the country's crime rate, Prime Minister Persad-Bissessar announced that “the time was right in this year of our 50th independence anniversary”.

“We will table legislation acceding to the criminal appellate jurisdiction of the CCJ.”

‘Half slave, half free’

Mrs Persad-Bissessar sought to explain the decision to retain the Privy Council for civil cases on the basis that “it inspires confidence in foreign investors”.

She added that keeping the Privy Council was “conducive to an investor-friendly climate at a time when the international economic order is changing and Trinidad and Tobago is attempting to woo foreign investment from the Brics [Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa] countries.”

What is being called the “half slave, half free” proposal was roundly condemned by former Trinidadian Chief Justice Michael de la Bastide, who said it would be an unworkable proposition.

Jamaica’s Mr Patterson noted that the Caricom Treaty which established the CCJ would have to be amended, as it does not provide for partial accession to the Caribbean Court in its appellate jurisdiction.

“If you try to bifurcate the jurisdiction of the Court [CCJ], you would end up in a situation where there is an appeal on a criminal matter before the Caribbean Court of Justice and then the disappointed litigant would simply file a constitutional motion saying he or she had been deprived of some constitutional right,” Mr Patterson told Caribbean Intelligence©.

“And that would mean that the motion would have to go before the Privy Council, as the British Court would still have jurisdiction over civil matters.”

“There can be no valid reason why the CCJ cannot be asked by its two most populous member states, who have contributed substantially to its funding, why the CCJ cannot be asked to take responsibility for its final jurisdiction in full,” said Mr Patterson.

Guaranteed independence

On the issue of the court’s independence, Mr Patterson said that the CCJ did not have to go cap-in-hand for funding.

It is funded in perpetuity by a US$100m trust fund, arranged by the Caribbean Development Bank, while member states pay back the loan.

He noted, too, that given the process of having a Caribbean Judicial and Legal Service Commission responsible for appointing judges, with the president of the court decided by Caricom leaders, “the Court is well structured and no one can successfully claim to the contrary.”

However, the former Jamaican prime minister warned: “Were [the CCJ] to fail, the structures of unity it supports would be endangered.”

In its original jurisdiction, the CCJ was established by the Caricom Treaty to be the sole arbiter in trade disputes involving countries and companies in the Caricom Single Market and Economy.

‘Stop lingering’

Taking his cue from Lord Nicholas Phillips’ advice to

“abolish appeals to the Privy Council and set up their own final courts of appeal instead”, veteran Caribbean regionalist Sir Shridath Ramphal has advised regional governments “to stop lingering on the doorstep of colonialism.”

The former Commonwealth Secretary-General has said: “If we continue to loiter, the interests of law in the Commonwealth will almost certainly require removal off the doorstep of the Privy Council.”