By Debbie Ransome

Going beyond the basic storyline to dig deeper into the Haitian reality and how it gets reported, this

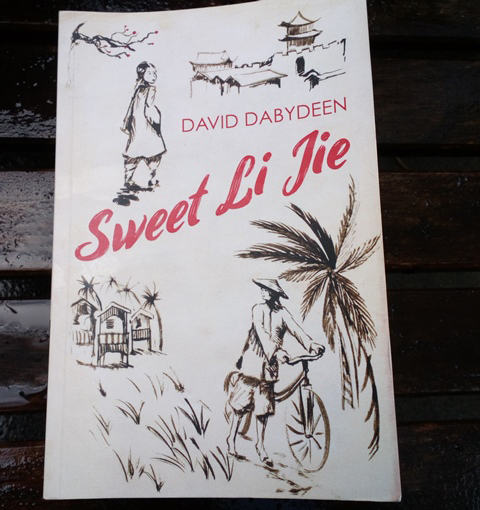

Caribbean Intelligence review of Sweet Li Jie by David Dabydeen

Review by Debbie Ransome, Managing Editor, Caribbean Intelligence

From the first page of this book, you are plunged into the passions and ambitions of people in 1870s China and Guyana, held together by one man’s longing for, and love letters to, the eponymous Sweet Li Jie.

The writer of the letters, cloth merchant “Suitor Jia Yun”, is a product of Wuhan, deep in rural China, where emperors, warlords and the British have fought for control and divided up the country and its resources, often in brutal ways.

Having sworn his love for Sweet Li Jie, Jia Yun makes the journey of many of his countrymen at the time to post-slavery British Guiana. There, he finds himself carving out a life in the jungles of Demerara, where African, Indian and Chinese migrants seek to make the mark on the territory’s rough and challenging terrain.

It's the sweet innocence of his love letters back to Sweet Li Jie that provide an evocative tale of a newly emerging country, with all to play for and the winner-takes-all mentality from all those around him.

Like Dickens’s Martin Chuzzlewit, where the main character leaves England and nearly dies in an Ohio swamp called Eden, the harshness of the yet-to-be-tamed terrain in colonial Guyana is somehow lightened by the characters we meet during the journey.

One of the most entertaining is Reverend Choy - a pastor of Prospect Town, who would not sit awkwardly in a modern day setting of rural slavery, greed and exploitation. Dabydeen writes:

Reverend Choy had about two hundred pigs on his farm. As a pastor he worked for the Demerara Anglican Missionary Society, and the pigs were all branded DAMS. Reverend Choy, though not their owner, was their steward. The Chronicle praised him for his work with pigs and people. [p129]

We are given a sense of the emerging Demerara region from “light-skinned Negro” Harris, whose wisdom paints the setting for the characters Jia Yun will have to deal with as he sets up a business in the area:

“Why the British settle here is sheer madness!” Harris said, relaxing the reins and letting the donkey make its own way to my house. “They slave the black people from Africa to make plantation and now they harvest coolie from India for the same. Chinese too weak for the work. The British give up on them. Coolie can get free passage home when five-year contract expire, but most of them stay. Why? They dream of gold like everybody else. Every few years there is a rush to the jungle, rumours of how so and so find gold, but in truth the only glow in their face is from jaundice.” [p48-49]

The underlying ambition in this new world is to recreate yourself away from your place of origin. People of every colour and race have a desire to escape, remake themselves and, possibly, return home rich. Dabydeen has a way of making you sympathise with the protagonists, rather than laugh at them.

Jia Yun writes to his sweetheart:

Gold was everywhere and yet nowhere. Demerara was the place the old adventurers called El Dorado, but no one ever found the City of Gold. [p100]

In the series of letters from the Chinese suitor, we get a sense of the harshness of the landscape and the people. We’re told that “the Chinese wilted under the heat and the whip”. When a town is left with all its money stolen, the residents find that their year-ahead rent has also gone. In the absence of the absconded custodian, the real owners find their homes repossessed and the dreams built up over years wiped out in no time at all in this colonial zero-sum game.

Even the kindness is dispensed in the style of an apparent student of progressivism(the political philosphy and movenent that sought to advance the human condition through social reform) in the character of the well-intentioned British doctor, Richmond. He saves people from cholera on the boat from China, ignoring the danger to himself. However, Dr Richmond has no qualms about sketching naked Chinese women on board the ship - “No faces. Have you noticed?” - to help his nature studies. Dr Richmond tells Jia Yun: “Mercy is our calling. And to educate. These sketches will show what Chinese bodies look like – the women’s. We know the men’s since we work so many to exhaustion, but your women are hidden away; they nurture fantasies in my people’s minds.”[p35]

This is a hard-to-put-down book, using the established epistolary technique of telling the main protagonist’s story through letters alongside internal monologue to paint a compelling tale of life in 1870s China and Guyana.

I won’t give away the endings to the various love stories which weave through the novel. You’ll have to embark on that journey yourself.

Sweet Li Jie by David Dabydeen, Peepal Tree Press, publication on 10 October, 2024.

By Debbie Ransome

Going beyond the basic storyline to dig deeper into the Haitian reality and how it gets reported, this

[photo: Patti Smith & Winston Rodney, cred Ted Bafaloukos]

In a year of global challenges and fall-out, we at Caribbean Intelligence© have focused on the aspirational side of Caribbean life.